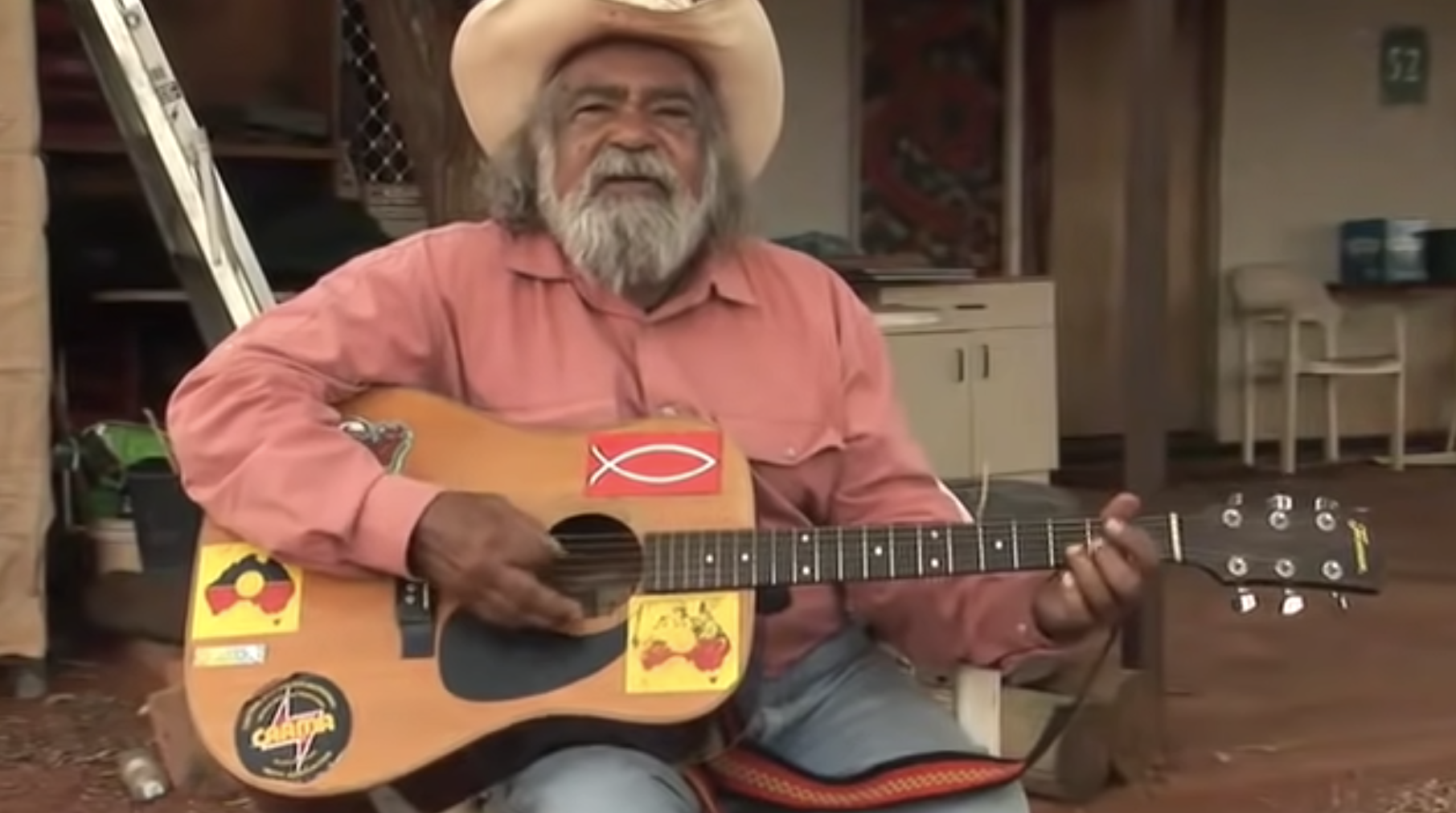

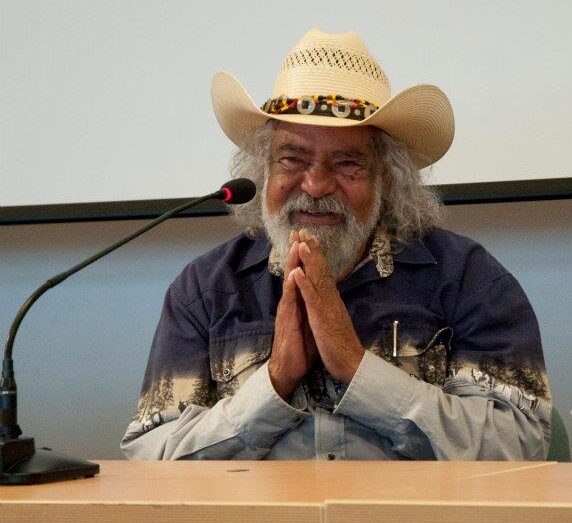

Uncle (Tjilpi) Bob Randall

Uncle Bob Randall (1929 -2015) was an Anangu man, a Tjilpi (special teaching uncle) of the Yankunytjatjara Nation of Central Australia, and one of the listed Traditional Custodians of the desert area that includes the special sites, Uluru and Kata Tjuta.

Born in the bush at Middleton Pond, on Tempe Downs Station in the Northern Territory, Uncle Bob was raised in the traditional way, on country, until about the age of 8 when he was taken away from his mother, his land, and his family. The Australian government of that time had an assimilation policy that ordered the removal of half-caste children from their families. Uncle Bob had a Yankunytjatjara mother and a European father.

He became one of more than 100,000 children who came to be known as The Stolen Generations. The Stolen Generation was a period in Australia’s history where Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their families by the government.

Young Bob was taken to an institution called The Bungalow in Alice Springs, and later sent to a Methodist Mission reservation on Croker Island off the north coast of Australia. As a child, Bob had no choice but to learn to fit into the European culture of the mission. But while the missionaries discouraged the 100 or so mission kids from having contact with ‘full blood’ Aboriginal people, young Bob continually found ways to connect with the local Aboriginal people who lived traditionally.

Throughout his time on the reservation Bob was fortunate to be adopted by the Iwaidja people of Croker Island, the Gunwingku people of western Arnhem Land, and the Gupapingu people of Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island).

They taught him their sacred lore, hunting and survival skills, and their traditions such that Uncle Bob, even as a boy and young man, was able to retain his Aboriginal identity.

As Uncle Bob later wrote in his autobiography, Songman, “Even though their stories are different from those of the Yankunytjatjara, they share the same reverence for the ancestral time of creation, and the naturalness of life, and the secret Law of the Rainbow Serpent, known as Ngalyod in western Arnhem Land. Although I was never able to undertake the traditional initiations of my Yankunytjatjara people, through which the lore is passed on, I was able to receive a great deal of this learning through my extended families of eastern and western Arnhem Land. I am not just a man of the desert, but also of saltwater country, and in this I am doubly blessed.”

The island mission had no record of Uncle Bob’s family, land of origin, or Aboriginal name. His records read, “Mother unknown, father unknown, tribe unknown.” When forced to leave Croker Island, upon arriving by boat on the mainland with wife and baby, Uncle Bob had no home or family to go to and had to learn how to live in urban Darwin, between two cultures. He took various jobs including as a gardener and hospital aide and eventually, motivated to help his people, he became a counsellor. Over time, with growing concern for the wellbeing of all, Uncle Bob focused his attentions on education and became a cultural teacher, story songwriter, performer, author, and tireless advocate and spokesperson for Aboriginal people and for the rights of all Nature.

As a teacher Uncle Bob helped establish the Adelaide Community College for Aboriginal people and became a cultural lecturer. He established Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Centres at Australian National University, the University of Canberra, and the University of Wollongong. He was a cultural educator at the Institute for Aboriginal Development (IAD) in Alice Springs and served as the Director of the Northern Territory Legal Aid Service in Alice Springs.

In the early 1970s, Uncle Bob earned widespread recognition for his song, “Brown Skin Baby,” which focused national and international attention on the issues of the Stolen Generations and opened the door for Indigenous story songwriters throughout Australia. The song led to the filming of a documentary by the same name that won the Bronze Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Bob’s lifelong efforts to retain Aboriginal culture and restore equal rights for all living were recognised in 1999 when he was named NAIDOC’s “Person of the Year.”

After many years of searching, Uncle Bob found his family and home and eventually returned to his country to live at Mutitjulu Community, beside Uluru. As the “Brown Skin Baby” song details, Uncle Bob never saw his mother again. He also obtained the work log diary of Constable McKinnon, the infamous policeman who stole him in 1938. McKinnon’s diary confirmed that young Bob was listed along with the names of the many Aboriginal prisoners who, with chains around their necks walked behind camels for three-and-a-half weeks in the December summer heat. They’d been arrested for killing cattle. When they arrived in Alice Springs, young Bob was separated from his family and put into the Bungalow Institution for what the government termed “half-caste” children.

Uncle Bob recorded his life story in an autobiography, Songman, published in 2003. His other published works included the books, Stories from Country, Nyunti Ninti and Tracker Tjugingji.

In 2004, he was inducted into the NT Indigenous Music Hall of fame, recognising the historical significance of his classic story songs.

In 2006, with the loving support of his Sandhill Rd Productions family, Uncle Bob wrote, narrated, and co-produced with Melanie Hogan the documentary film, Kanyini.

In 2013 Uncle Bob appeared and performed in Mbantua Festival’s outdoor performance, Bungalow Song, followed by an appearance in John Pilger’s 2014 documentary film, Utopia, and released two documentary films, appearing with Andrew Harvey, Songman and Living Kanyini

Over decades, Uncle Bob shared his teachings everywhere he could. He spoke and taught throughout the world presenting Aboriginal cultural perspectives on living based on the Kanyini Principles which he was raised with, both in the desert and in Saltwater Country. The Kanyini Teachings are founded in ancient wisdom ways of caring for each other, all living, and the environment with unconditional love and responsibility. Seeing the decline of the quality of life for all beings in the world, his vision and subsequent directive included sharing and passing down the Kanyini Teachings for all people of the world saying, “Kanyini is the key to our survival.”

As a bridge between cultures and world nations, Uncle Bob created pathways of understanding so all peoples can live and learn together, healing the past through shared experience in the present.

Uncle Bob’s legacy calls all peoples to live together as one family on Mother Earth. His teachings call Indigenous people to reclaim their Aboriginal identities and re-gain lives of purpose, so that the relevance of ancient wisdom in modern context is understood and valued. With two-way learning and working together we can preserve Indigenous cultural knowledge in order to heal together, restore environmental sustainability and well-being for all life, reclaim sacred relationships within life, and once again live in the natural order of interconnectedness, in peace and harmony with each other and all creation.

Bob passed away on 12 May 2015, aged approximately 81. Before his passing in 2015, Uncle Bob instructed Barbara, as his wife, to “get these teachings out to the world.”

His legacy lives on forever through these teachings.